Insignia of the Golden Fleece

Insignia of the Golden Fleece

With the

division of the Order into Spanish and Austrian Orders the nature of the insignia

took very different directions in the two lands. In Spain the motto was never

used on the briquette and the fleece was seen in full profile showing only one

horn and eye. The shapes of the pieces, especially the briquette, became very

ornate and abstract -- a mixture of Moorish and Baroque arabesques. In Austria

the motto was always used, the pieces kept their traditional shapes and, starting

with the late 18th century, the fleece was seen with the head twisted to the front

to show both horns and eyes, and by around 1860 this was the rule for Austrian

bijous. The c. 1850 fleece seen at the left confounds all this reason as it has

essential elements of both Spain and Austria.The fleece is in profile and, almost

uniquely, swings loose in its strap, and the briquette and pierre a fois both

have turned into a baroque ribbon. The flames are of a well known 19th century

Spanish layered style. Yet in contrast it bears the motto in a clear, mid-19th

century sans serif style as do Austrian fleeces, and the ribbon ring is in the

grooved Austrian style of 1814-1850. The most interesting part is that the pierre

a fois is in painted, fired enamel rather than gold sculpture -- I know of no

other example thus. How better than to start with an example that transcends the

rules.

With the

division of the Order into Spanish and Austrian Orders the nature of the insignia

took very different directions in the two lands. In Spain the motto was never

used on the briquette and the fleece was seen in full profile showing only one

horn and eye. The shapes of the pieces, especially the briquette, became very

ornate and abstract -- a mixture of Moorish and Baroque arabesques. In Austria

the motto was always used, the pieces kept their traditional shapes and, starting

with the late 18th century, the fleece was seen with the head twisted to the front

to show both horns and eyes, and by around 1860 this was the rule for Austrian

bijous. The c. 1850 fleece seen at the left confounds all this reason as it has

essential elements of both Spain and Austria.The fleece is in profile and, almost

uniquely, swings loose in its strap, and the briquette and pierre a fois both

have turned into a baroque ribbon. The flames are of a well known 19th century

Spanish layered style. Yet in contrast it bears the motto in a clear, mid-19th

century sans serif style as do Austrian fleeces, and the ribbon ring is in the

grooved Austrian style of 1814-1850. The most interesting part is that the pierre

a fois is in painted, fired enamel rather than gold sculpture -- I know of no

other example thus. How better than to start with an example that transcends the

rules.

Examples

from these early days before the splitting of the Order into two branches are

almost never seen. The only one we have any certain identity for, beyond one

in the Bayarische National Museum, is this Netherlands fleece found by accident

at Aldenhaag in the central Netherlands some 40 years ago. The fleece was found

at in the ruins of a castle that belonged to Claes Vijgh, a relative of Floris

van Egmond (seen at right) and both members of the Golden Fleece. Floris’

son Maximillian was a member as well, and the fleece belonged to one of these

Egmonds. In 1574-75 the Spanish under the Duke of Alba burned the castles and

the Betuwe region all around in their war against the Dutch protestants, and

this fleece ws likely lost in the sacking of the castle at Soelen-Aldenhaag

in 1574. There this fleece lay until Willem H. van Duijn found in while on a

picnic from his nearby school.

Examples

from these early days before the splitting of the Order into two branches are

almost never seen. The only one we have any certain identity for, beyond one

in the Bayarische National Museum, is this Netherlands fleece found by accident

at Aldenhaag in the central Netherlands some 40 years ago. The fleece was found

at in the ruins of a castle that belonged to Claes Vijgh, a relative of Floris

van Egmond (seen at right) and both members of the Golden Fleece. Floris’

son Maximillian was a member as well, and the fleece belonged to one of these

Egmonds. In 1574-75 the Spanish under the Duke of Alba burned the castles and

the Betuwe region all around in their war against the Dutch protestants, and

this fleece ws likely lost in the sacking of the castle at Soelen-Aldenhaag

in 1574. There this fleece lay until Willem H. van Duijn found in while on a

picnic from his nearby school.

This is an early form of the fleece called the standing ram fleece, a genuine and very old style fleece peculiar to the low countries, Spain and Portugal in the time of Charles V. An early version of the style is seen in a painting of Charles the Rash where the fleece is fairly solid bodied and upright. It is seen fully developed in a Flemish sculpture of the young Charles V in 1522, and by mid century was becoming obsolete. Unlike the later fleeces, whose pinched middle shows that they are a mere skin of gold, these early ones are almost a standing live animal held by a hoisting belt. Their feet extend straight down, ready to stand when they touch ground. They are also usually quite large, this one being 5 cm across. More information and graphics can be seen at the Aldenhaag Fleece pages.

The

insignia of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece. The collar is modern and

dates from 1900-1950, and it was acquired in Madrid by an American military

officer in the early 1950s. It is in silver gilt and is the proper Alpohonse

XIII type. The neck decoration is c. 1900 with a sapphire in the "pierre

a fois". The miniature, in gold and with original ribbon, dates from c.

1860-1890.

The

insignia of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece. The collar is modern and

dates from 1900-1950, and it was acquired in Madrid by an American military

officer in the early 1950s. It is in silver gilt and is the proper Alpohonse

XIII type. The neck decoration is c. 1900 with a sapphire in the "pierre

a fois". The miniature, in gold and with original ribbon, dates from c.

1860-1890.

Elements of the Spanish insignia to be noted are the fleece being in full profile,

the stylized flames turning into a "mass", and the entirely abstract

"briquet" that no longer resembles anything this side of the Alhambra.

The modern Austrian fleece has the head twisted to show both eyes and horns,

even when the fleece as a whole is in profile. The individual flames are more

distinct in the Austrian fleece and the "briquet" is clearly the fire

steel of the house of Burgundy and shows the motto on full size bijous. There

are clear differences in the style of the fleece both in sculpture and in hanging

form. The fleece on this bijou and collar are the tight, slender leg toison

of the modern Spanish order. The Austrian is a plumper, more substantial beast

in the modern form. Anciently all were woolier and more clearly delineated,

and many of the original fleeces took the form of the complete ram rather than

only its hanging fleece. (Miniature from the chancelier's collection; bijou

in a private collection; collar in a private American collection.)

Two Jeweled fleeces from Bavaria -- mid 18th century

Probably

created for Maximillian II, Duke and Elector of Bavaria (Spanish knight no.

718), these two gold bijous are richly set with diamonds, garnet, sapphire and

ruby. They date from the mid 18th century and are probably of Bavarian manufacture.

The one with blue stones has the famous Wittelsbach Blue diamond in the top

part. It is with objects such as these that we can see the truth in the statement

that by this period orders were the "jewelry of European noblemen".

Their original and more devotional origins were long forgotten and they became

only another status symbol. Perhaps inevitable in a modern state but also the

beginning of their decay and ultimate disappearance.

Probably

created for Maximillian II, Duke and Elector of Bavaria (Spanish knight no.

718), these two gold bijous are richly set with diamonds, garnet, sapphire and

ruby. They date from the mid 18th century and are probably of Bavarian manufacture.

The one with blue stones has the famous Wittelsbach Blue diamond in the top

part. It is with objects such as these that we can see the truth in the statement

that by this period orders were the "jewelry of European noblemen".

Their original and more devotional origins were long forgotten and they became

only another status symbol. Perhaps inevitable in a modern state but also the

beginning of their decay and ultimate disappearance.

An

interesting and very early mid-17th to 18th century brass-gilt bijou. It is

likely of Portugese or Spanish origin based on the design and style, although

the ball mount for the ring seems French. Owing to the dangers of loss and cost

of gold, brass-gilt and bronze-gilt fleeces were common in the 16th to early

18th centuries, especially for wear with armor. Often very large (to 9 cm. wide)

they saw heavy daily usage and are very scarce. The fleece style here, of a

life-like ram standing, is seen in pieces worn by Charles V in the early 16th

century and is an old Flemishish form taken to Spain & Portugal by Charles

V and his courtiers. It should be compared to the Aldenhaag Fleece above that

may have belonged to Charles V himself. The peculiar curving "pierre a

fois" flames are also Hispanic in style, as is the stylized firesteel above.

The firesteel arabesque contains a decorative "pierre a fois" design

similar to printer's fleurons of the late 17th century. The mounts of this piece

show long wearing and several old repairs consistent with its age. The flames

are set with old mine cut crystal or pastes, but having an early and simple

top table looking towards the later brilliant cut, and the central amethyst

hints at the Portugese mines in Brazil, as does the overall large and elaborate

style. The flat cut of the flames and mounting of the stones matches the Bavarian

pieces shown above that date to the mid 18th century. In the 17th, and more

so in the 18th, centuries the great and wealthy often had suites of bijous,

each with different color jewels to match their different clothing colors. On

the left, the entire Bijou; on the right the fine arabesque firestone within

the firesteel. (From the chancelier's collection)

An

interesting and very early mid-17th to 18th century brass-gilt bijou. It is

likely of Portugese or Spanish origin based on the design and style, although

the ball mount for the ring seems French. Owing to the dangers of loss and cost

of gold, brass-gilt and bronze-gilt fleeces were common in the 16th to early

18th centuries, especially for wear with armor. Often very large (to 9 cm. wide)

they saw heavy daily usage and are very scarce. The fleece style here, of a

life-like ram standing, is seen in pieces worn by Charles V in the early 16th

century and is an old Flemishish form taken to Spain & Portugal by Charles

V and his courtiers. It should be compared to the Aldenhaag Fleece above that

may have belonged to Charles V himself. The peculiar curving "pierre a

fois" flames are also Hispanic in style, as is the stylized firesteel above.

The firesteel arabesque contains a decorative "pierre a fois" design

similar to printer's fleurons of the late 17th century. The mounts of this piece

show long wearing and several old repairs consistent with its age. The flames

are set with old mine cut crystal or pastes, but having an early and simple

top table looking towards the later brilliant cut, and the central amethyst

hints at the Portugese mines in Brazil, as does the overall large and elaborate

style. The flat cut of the flames and mounting of the stones matches the Bavarian

pieces shown above that date to the mid 18th century. In the 17th, and more

so in the 18th, centuries the great and wealthy often had suites of bijous,

each with different color jewels to match their different clothing colors. On

the left, the entire Bijou; on the right the fine arabesque firestone within

the firesteel. (From the chancelier's collection)

More recent research into the history of the ancient Aldenhaag Fleece and the history of the standing ram form, of which this is one example, seems to point to this bijou dating to c. 1700 when the Bourbons received the crown of Spain. They then briefly revived old forms of the fleece based on examples from the order treasury. Portraits of this period of members from Spain and France consistently show use of the standing ram form at least in art, and this bijou provides a material example of those shown. When Phillip V took the throne and became head of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece he was not yet a member of the order. As there was little time to make new insignia he seems to have taken older, standing ram style fleeces from the treasury of the order. This style was then copied for a time by other Bourbon recipients. Once it became an artistic style the standing ram continued to be depicted in formal paintings and sculpture of such members until the Revolution. More information can be found on our The Standing Ram & Charles V page. So far as we know this is the only surviving Bourbon revival fleece, and the century and a half of violence from the French Revolution to the Spanish Civil War must have destroyed the others. This being a Bourbon antiquarian form would help explain the use of the fleuron for a briquet and the French style ball mount on the top.

An

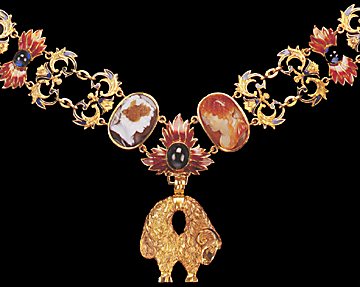

interesting and eccentric private Spanish Fleece Collar in gold, synthetic sapphire,

enamel and cameos from the early 20th century. The collar has only 18 sets of

firestones and paired fire steels and so is short of the usual 28 sets. The

cameos are of late 18th century manufacture. From a European Royal House.

An

interesting and eccentric private Spanish Fleece Collar in gold, synthetic sapphire,

enamel and cameos from the early 20th century. The collar has only 18 sets of

firestones and paired fire steels and so is short of the usual 28 sets. The

cameos are of late 18th century manufacture. From a European Royal House. A late

19th century badge in gold and enamel of the greffier of the Spanish Order of

the Golden Fleece. Although fleeces in various forms come to market from time

to time, the badges of officials are very rare.From an European Catalog.

A late

19th century badge in gold and enamel of the greffier of the Spanish Order of

the Golden Fleece. Although fleeces in various forms come to market from time

to time, the badges of officials are very rare.From an European Catalog.

Gold

badge of office of the Grand Inquisitor, or head of the Church Council of

the Spanish Holy Office, that is an interesting association item with the Golden

Fleece. From the last quarter of the 17th century this officer was Balthasar

Sarmiento de Mendoza y Sandoval, 5th Marquis of Camarosa, Bishop of Segovia

and Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece No. 476. The badge is closely dated

to c. 1700 and so is almost certainly his.

Gold

badge of office of the Grand Inquisitor, or head of the Church Council of

the Spanish Holy Office, that is an interesting association item with the Golden

Fleece. From the last quarter of the 17th century this officer was Balthasar

Sarmiento de Mendoza y Sandoval, 5th Marquis of Camarosa, Bishop of Segovia

and Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece No. 476. The badge is closely dated

to c. 1700 and so is almost certainly his.

The insignia

of the Austrian Order of the Golden Fleece remained more traditional than the

Spanish ones. The one illustrated here is the standard full Austrian bijou of

the order in finely chisled gold dating from the mid ninteenth century. It has

all elements including the fleece, pierre a fois, briquet with motto and Jason

illustration and the decorative knot piece for the ribbon. Suspended from the

neck by the red ribbon of the order. This example reflects the highest quality

of the standard fleece. Interestingly, although clearly an Austrian bijou the

fleece itself is of Spanish style with the rams head shown in profile rather than

frontal (also see the item below). From a German noble family

The insignia

of the Austrian Order of the Golden Fleece remained more traditional than the

Spanish ones. The one illustrated here is the standard full Austrian bijou of

the order in finely chisled gold dating from the mid ninteenth century. It has

all elements including the fleece, pierre a fois, briquet with motto and Jason

illustration and the decorative knot piece for the ribbon. Suspended from the

neck by the red ribbon of the order. This example reflects the highest quality

of the standard fleece. Interestingly, although clearly an Austrian bijou the

fleece itself is of Spanish style with the rams head shown in profile rather than

frontal (also see the item below). From a German noble family

A lovely

and rare Austrian baroque bijou from around 1750 in gold and enamel. The influence

of the Spanish Fleece can be seen in the stylized fire steel without the motto

that the Austrian pieces invariably bore at a later date. Compare the near standing

and lifelike fleece here with that of the Portugese/Spanish one above. (From

the Spada collection)

A lovely

and rare Austrian baroque bijou from around 1750 in gold and enamel. The influence

of the Spanish Fleece can be seen in the stylized fire steel without the motto

that the Austrian pieces invariably bore at a later date. Compare the near standing

and lifelike fleece here with that of the Portugese/Spanish one above. (From

the Spada collection) The

Schwarzenberg Princen Fleece is a masterfully chased gold Fleece in a Prinzen

size (20 mm. wide) made for Joseph Adam, Prince of Schwarzenberg between 1740

and 1780. The opening in the back of the clasp indicates that at one time it was

attached to the elements of the full bijou, but they are long lost or the Fleece

was deliberately detached for wearing as a knopfloch. The current gold mounting

wire is old and matches those on other old Austrian medals. The remainder of these

unique Fleeces were in the collection of Dr. Spada, and are likely lost forever

following their theft some years ago. They may, however, still be seen in his

"Onori e Glorie" publication. For more about the Schwarzenbergs and

their history see the Schwarzenberg page.

(In the collection of the Cancelier.)

The

Schwarzenberg Princen Fleece is a masterfully chased gold Fleece in a Prinzen

size (20 mm. wide) made for Joseph Adam, Prince of Schwarzenberg between 1740

and 1780. The opening in the back of the clasp indicates that at one time it was

attached to the elements of the full bijou, but they are long lost or the Fleece

was deliberately detached for wearing as a knopfloch. The current gold mounting

wire is old and matches those on other old Austrian medals. The remainder of these

unique Fleeces were in the collection of Dr. Spada, and are likely lost forever

following their theft some years ago. They may, however, still be seen in his

"Onori e Glorie" publication. For more about the Schwarzenbergs and

their history see the Schwarzenberg page.

(In the collection of the Cancelier.)

It’s provenance is from a Hungarian antique dealer. He obtained it from the recent sale by a Vienna theater of all costumes and props when they lost the use of their building which they had had for a century. The theater purchased the item on the Vienna second hand market generations ago; most likely in 1920-1940. The theater also had original Napoleonic uniforms with period orders on them, indicating their use of numerous authentic antiques as props.

The uniface bijou is the norm for all modern Spanish badges, and most of those set with jewels as well, but is seldom seen in Austrian Golden Fleece bijous. This one is also interesting due to the elongated fleece that was previously sparingly used by the Habsburgs in the 16th century and then disappears until this bijou. At least two modern cast copies of this style fleece are known, but in much inferior quality. One was in on eBay in France and the other in the U.S. An elongated fleece just like this one is also is known on an Austrian door knocker from late Imperial times.

Although

known to be prior to WW I by its excellent provenance, comparison with older

uniface official badges strongly suggests this bijou is late 18th century. At

right is the back of an Austrian 1767 cast and gilt brass cap badge for infantry

that shows the same peculiar indents and pressing of the back. Perhaps this

was done to save metal or to obtain a better casting, but it is not done today.

All late 19th century and 20th century uniface orders I have seen have flat

and very smooth backs; neither this cap badge nor the uniface fleece above are

made this way and seem much more antique and hand-made.

A

wonderful enameled 17th century “jewel” of a holder or officer of the Golden

Fleece. On the obverse we see Emperor Leopold of Austria (clearly showing the

“Habsburg Jaw”), and on the back the Austrian coat of arms with

Leopold’s initials L(eopolus) I(mperator). Above a crown and hanging below

a rich, golden fleece. This item was purchased in Paris by one of our correspondents.

Such pieces were often a gift of the ruler shown to a specially favored subject.

(In a private French collection)

A

wonderful enameled 17th century “jewel” of a holder or officer of the Golden

Fleece. On the obverse we see Emperor Leopold of Austria (clearly showing the

“Habsburg Jaw”), and on the back the Austrian coat of arms with

Leopold’s initials L(eopolus) I(mperator). Above a crown and hanging below

a rich, golden fleece. This item was purchased in Paris by one of our correspondents.

Such pieces were often a gift of the ruler shown to a specially favored subject.

(In a private French collection)

The miniature

and chain is the daily wearing form in civilian or official undress. The Austrian

miniature fleece to the right is of solid gold and excellent quality dating from

the late ninteenth century. The chain, in bronze gilt, is later and of much lesser

quality. (From the collection of Joy Hawkes)

The miniature

and chain is the daily wearing form in civilian or official undress. The Austrian

miniature fleece to the right is of solid gold and excellent quality dating from

the late ninteenth century. The chain, in bronze gilt, is later and of much lesser

quality. (From the collection of Joy Hawkes)  A very

artistic Austrian miniature fleece in gold with the ram's head turned 3/4 left.

I have seen two other miniatures with this very 3-dimensional sculpting. Early

20th century.(In the collection of the Cancelier)

A very

artistic Austrian miniature fleece in gold with the ram's head turned 3/4 left.

I have seen two other miniatures with this very 3-dimensional sculpting. Early

20th century.(In the collection of the Cancelier) Unlike

the Austrian miniture collar above, which is held in place by a fancy button

and a pin, this modern (c. 1950s-60s) Spanish miniature collar is a complete

circle that hangs by a button alone. Made by an official court jeweler in Madrid.